Peter Milton Walsh es el cantante y compositor de The Apartments. Formó la banda en Brisbane, Australia, en 1978. El primer lanzamiento de The Apartments, un EP “the return of the hypnotist”, fue lanzado en el sello The Go Betweens, Able en 1979. Walsh luego se mudó a Nueva York y después a Londres, donde grabó “The evening visits”, un LP para Rough Trade en 1985. Desde entonces, Peter Milton Walsh ha tocado solo o con su banda en todas partes, desde San Francisco hasta Sydney, desde Copenhague hasta Colonia. En octubre de 2023, realizará una serie de exposiciones individuales en lugares selectos de Italia, Francia y Portugal. Un nuevo álbum de Apartments, That’s What the Music is For, se lanzará en 2024. Además, el álbum Apartments 1997 se publicará en vinilo por primera vez en noviembre de 2023.

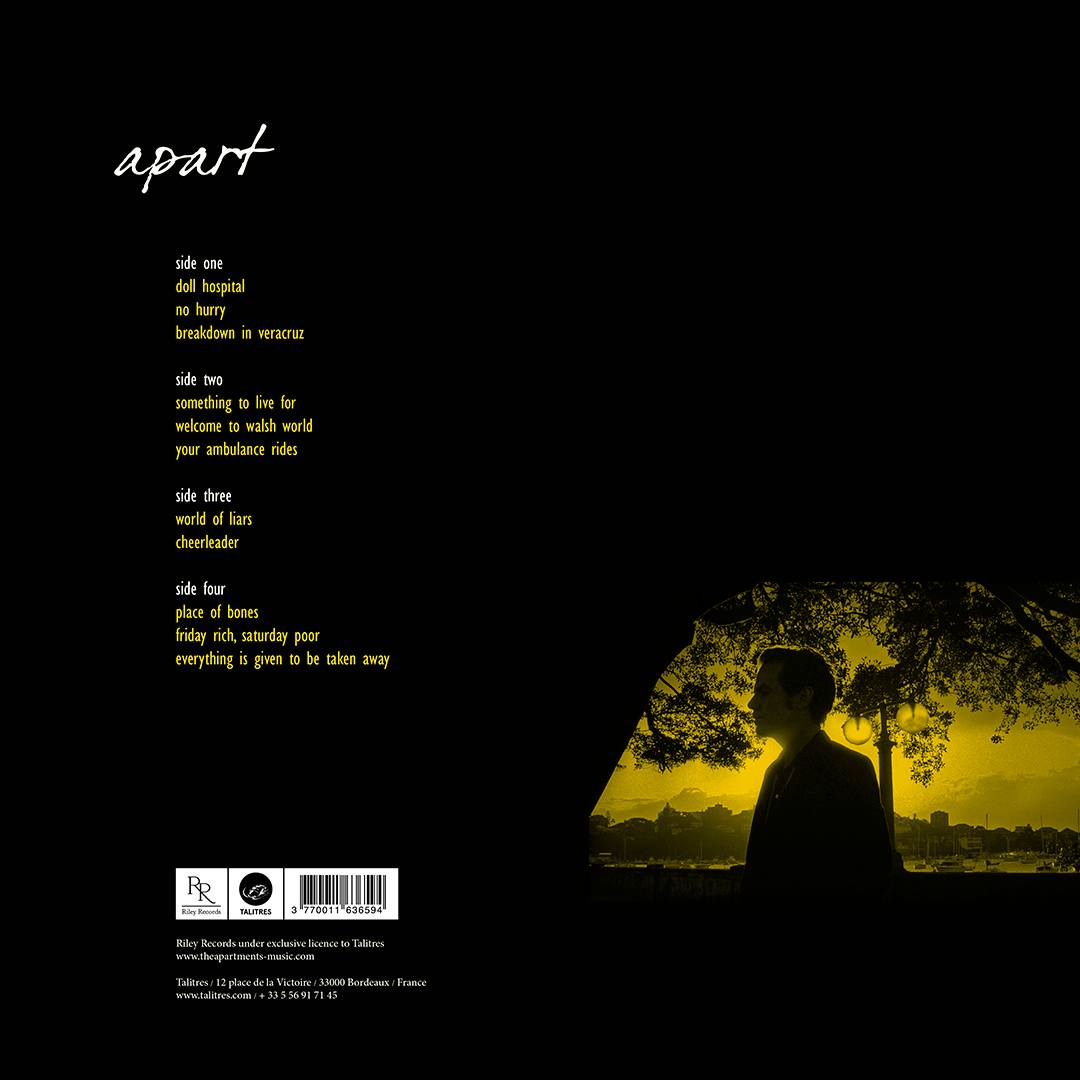

Peter Milton Walsh is the singer/songwriter from The Apartments. He formed the band in Brisbane, Australia, in 1978. The Apartments first release, an EP the return of the hypnotist was released on The Go Betweens Able label in 1979. Walsh then moved to New York, then to London where he recorded the evening visits… LP for Rough Trade in 1985. Since that time, Peter Milton Walsh has played either solo or with his band everywhere from San Francisco to Sydney, Copenhagen to Cologne. In October 2023, he is doing a run of solo shows at select venues in Italy, France and Portugal. A new Apartments album, That’s What the Music is For is due for release in 2024. The Apartments 1997 album, apart, will be issued on vinyl for the first time in November 2023.

https://www.instagram.com/initialspmw/

https://www.theapartments-music.com/

https://www.facebook.com/theapartments/

ENTREVISTA A PETER MILTON WALSH

What is your first album bought?

¿Cuál es tu primer álbum comprado?

When I was a kid, albums were a very big deal. They cost a lot, so you didn’t have many. People would lend albums to one another. A guy I went to high school with, who was from Canada and played a 12 string dreadnought guitar, lent me his Gordon Lightfoot The Way I Feel and Ramblin’ Jack Eliot Young Brigham albums. He forgot to get them from me before he moved back to Canada, so they were my first albums.

Ramblin’ Jack’s If I Were a Carpenter was the first fingerpicking song I tried, though Gordon Lightfoot also had a few. I lived with those albums, as I lived with every album because they were so hard to get. They were sacred objects. I would listen to them for weeks, months. You’d always end up spending so much time with an album that you knew its world, every detail of the cover and photos and credits and liner notes entirely, the sleeve, the artwork. You had drenched yourself in it. An album was a world. There was a strong sense of ritual and ceremony in putting an album on the turntable. It required “presence”. Even the static before a track began seemed full of promise, a prelude to a kiss. And while at night if you were home you could always turn the record over, listen to both sides, anytime you were in a rush or getting dressed before heading out, you’d have to choose which side you’d listen to. Because there was not enough time for both sides.

Cuando era niño, los álbumes eran muy importantes. Costaban mucho dinero, así que no tenía muchos. La gente se prestaba los discos unos a otros. Un chico con el que fui a la escuela secundaria que era de Canadá, tocaba una guitarra de 12 cuerdas. Una guitarra acústica y me prestó su disco de Gordon Lightfoot; The Way I Feel y el de Ramblin’ Jack Eliot; Young Brigham. Se olvidó de pedírmelos antes de regresar a Canadá, así que ¡fueron mis primeros álbumes!

If I Were a Carpenter de Ramblin’ Jack fue la primera canción sobre la que intenté imitar el punteo. Viví con esos álbumes, como viví con cada álbum porque eran tan difícil de conseguir. Eran objetos sagrados, los escucharía por semanas, meses. Siempre terminarías pasando mucho tiempo con un disco del que conocías su mundo, cada detalle de la portada, fotos, créditos y notas en su totalidad, esas portadas eran obras de arte. Cada disco era un mundo. Había un fuerte sentido de ritual y de ceremonia al poner un álbum en el tocadiscos. Requería “presencia”. Incluso la estática antes de que comenzara una pista parecía llena de promesas, como un preludio a un beso.

Por la noche cuando uno estuviera en casa siempre podrías poner el disco entero, escuchar ambos lados, ya que cada vez que tuviera prisa o me vistiera para salir, tendría que elegir qué lado escucharía. Porque no tenía nunca suficiente tiempo para escuchar ambas partes.

For a long time, I really only had compilation albums and greatest hits collections—High Tide & Green Grass, The Best of Mancini, Petula Clark, Manfred Mann, Hollies Greatest Hits, The Golden Hits of The Shangri-Las, Sandie Shaw, that kind of thing. The first album I paid for with my own money was Erik Satie— Entremont Conducts Satie, The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. I’d heard something from this playing in the background of a story on a Sunday night TV show called ‘Weekend Magazine’. The music was immediately mesmerising, haunting, so I wrote to the TV station to ask about the music they’d played. They wrote back! It was one of the Gymnopédies, either No. 1 or No. 3, I’m not sure, with this conductor and this orchestra. So I had to have it. In the record store, there was a listening booth, so you could work out if you were going to buy the record or not. This was in the 70s. After that I used to look for Satie in secondhand record stores but I never found anything that hit me quite the way the Gymnopédies did. It was also very significant to me that both the Gymnopédies and Ravel’s Pavane for a Dead Princess had both been referred to in poems by an Australian writer I really loved who died when he was 23, Michael Dransfield.

Durante mucho tiempo sólo tuve álbumes recopilatorios y grandes éxitos. collections—High Tide & Green Grass, lo mejor de Mancini, Petula Clark, Manfred Mann, Grandes éxitos de Hollies, Los éxitos de oro de los Shangri-Las, Sandie Shaw, ese tipo de cosas. El primer álbum que pagué con mi propio dinero fue Erik Satie. Entremont dirige a Satie, la Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. Había escuchado algo de aquella música sonando de fondo un domingo en una historia que salía en un programa de televisión nocturno llamado ‘Weekend Magazine’.

La música fue inmediatamente fascinante, inquietante, así que escribí a la televisión para preguntar sobre la música que había sonado. Y, ¡Me respondieron! Era una de las Gymnopédies, ya sea la número 1 o la número 3, no estoy seguro. Pero tenía que tenerlo. En la tienda de discos, había una cabina de escucha, por lo que podías decidir al escuchar si comprabas el disco o no. Aquello pasó en los años 70. Después de eso solía buscar discos de Satie de segunda mano en las tiendas de discos, pero nunca encontré nada que me impactara tanto. Las Gymnopédies lo hicieron. También fue muy significativo para mí que tanto las Gymnopédies y Pavana para una princesa muerta de Ravel habían sido mencionado en poemas de un escritor australiano que realmente amaba y que murió cuando tenía 23 años, Michael Dransfield.

¿Tu disco cuando te sientes nostálgico?

Your album when you are nostalgic?

Highway 61 Revisited.

¿Qué sonaría en tu funeral?

What would sound at your funeral?

The title song from the new Apartments album, to be released in 2024. That’s What the Music is For.

La canción principal del nuevo álbum Apartments, que se lanzará en 2024. That’s What the Music is For.

¿Tu banda sonora favorita?

Your favourite soundtrack?

Chinatown by Jerry Goldsmith. Although recently I heard Colpo Rovente by Piero Piccioni for the first time, and have have been playing that a lot.

Chinatown de Jerry Goldsmith. Aunque hace poco escuché a Colpo Rovente de Piero Piccioni por primera vez y he estado escuchando eso mucho.

¿Hay algún disco en particular que haya tenido un efecto en tu composición?

Is there a particular record that had an effect on your songwriting?

Mr Tambourine Man by Bob Dylan. I loved the song and did not understand it or at least not in the way I usually understood a song—I got it in a different way. It was teeming with interesting images, language and it was not so much a story as a mood. So that was a breakthrough for me. The song itself felt like an invitation to a voyage. I was so accustomed to songs—even earlier Bob Dylan songs for that matter—that were story songs. The songs I’d loved from listening to the radio were story songs. You knew exactly what was happening. Another thing those kind of songs had in common was that lyrically, they came from an older, adult world. That particular kind of realist storytelling was in the lyrics of people who wrote songs I entirely loved that I’d heard on the radio—like Hal David, say Walk on By or One Less Bell to Answer, Jackie Trent and Tony Hatch’s Downtown, Graham Gouldman’s No Milk Today.

Those songs were adult life as it had been for a previous generation. And Mr Tambourine Man was more like our world, not theirs. My life seemed less linear than this, it was constantly shifting, one impression to another—Mr Tambourine Man felt like that. I didn’t hear it when it was released, I know that it was years later. Pretty sure the first time was only after I’d left home at 18. And the album would have belonged to someone else. Hearing it round that time felt like permission to let my own songs take a different direction, lyrically anyway. Lyrics did not have to develop a a story along a line. A song could be like smoke, like a Raymond Chandler novel—all atmosphere. Or an Antonioni movie—something that floated through its own world that might not have made sense. There’s was songwriting before Dylan and songwriting after Dylan—he was one of those once-in-a-generation kind of artists who broke new ground. Mr Tambourine Man showed me that a song could be in the language and scenes and settings of our lives, not like my parents generation’s lives. Their world was so different to the one I moved in—“I know that evening’s empire has returned into sand…my weariness amazes me, I’m branded on my feet, I have no one to meet and the ancient empty street’s too dead for dreaming…” My own whirling world began turning up a lot more in my songs after Mr Tambourine Man.

Mr Tambourine Man de Bob Dylan. Me encantó la canción y no entenderla o al menos no de la forma en que normalmente entendía una canción; lo conseguí de otra manera. Estaba lleno de imágenes interesantes, de lenguaje y no era tanto una historia si no un estado de ánimo. Así que eso fue un avance para mí. La canción en sí parecía la invitación a un viaje. Estaba tan acostumbrado a las canciones (incluso canciones anteriores de Bob Dylan, todas importan, pero aquellas eran canciones sobre historias. Las canciones que me encantaron al escucharlas en la radio eran canciones sobre historias y sabías exactamente lo que estaba pasando. Otra cosa que ese tipo de canciones tenían en común era que líricamente, venían de un mundo más viejo y adulto. Ese tipo particular de realismo en la narración estaban en canciones que amaba completamente y que había escuchado en la radio, como Walk on By de Hal David o One Less Bell to Answer, el Downtown de Jackie Trent and Tony Hatch, No Milk Today de Graham Gouldman.

Esas canciones eran la vida adulta de una generación anterior. Y Mr Tambourine Man se parecía más a nuestro mundo, no al de ellos. Mi vida parecía menos lineal que aquello, estaba en constante cambio, una impresión a otro: el señor Tambourine Man me hizo sentirme así. No lo escuché cuando se estrenó, sé que fue años después. Estoy bastante seguro de que la primera vez fue sólo después de que me fui de casa a los 18 años. Y el disco había pertenecido a otra persona. Escucharlo en esa época me pareció un permiso para dejar que mis propias canciones tomaran el control y una dirección diferente, líricamente al menos. Las letras no tenían que desarrollarse como una historia lineal. Una canción podría ser como el humo, como una Novela de Raymond Chandler: todo atmósfera. O una película de Antonioni, algo que flotaba a través de su propio mundo que tal vez no hubiera tenido sentido. Hubo composiciones antes de Dylan y composiciones después de Dylan.

Fue uno de esos artistas únicos en una generación que abrieron nuevos caminos. Mr Tambourine Man me mostró que una canción podría estar en el idioma, en las escenas y escenarios de nuestras vidas, no como los de la generación o la vida de mis padres. Su mundo era tan diferente al que yo vivía: ““I know that evening’s empire has returned into sand…my weariness amazes me, I’m branded on my feet, I have no one to meet and the ancient empty street’s too dead for dreaming…” Mi propio mundo empezó a girar y aparecer mucho más en mis canciones después de Mr Tambourine Man.

¿Vinilo o CD? ¿Tu última compra?

Vinyl or CD? Your last purchase?

Both. Vinyl of Jokes and Trials by Ned Colette.

Ambos. Vinilo de Ned Colette titulado Jokes and Trials

¿Dónde escuchas música mayormente?

Where do you listen to the most music?

A room at the back of the house, where I have my piano, guitars and a desk. It’s a concrete floor, so I can’t lie down on it. Because that used to be my favourite place for listening—lying on the floor, my head between the speakers.

Una habitación en la parte trasera de la casa, donde tengo mi piano, guitarras y un escritorio. Es solo una habitación sin cama, así que es mi lugar favorito para escuchar música; tumbado en el suelo, con la cabeza entre los altavoces.

¿Cuál es el disco que más has escuchado durante la pandemia, o hasta resistir el confinamiento?

What is the record you have heard the most during the pandemic, or to resist confinement?

Cranes in the Sky by Solange. I must have played that track a hundred times. There was a woman, maybe in her late twenties, living on the first floor of the flats across the road. We would talk to her occasionally on the street. Due to social distancing laws during the pandemic, she had turned into this Juliet figure, standing out on her balcony in the afternoon from time to time, talking to some guy down on the street below visiting her. I was reading in bed late one night, my wife was in the shower, and Juliet came home on her bicycle—the streets seemed to be entirely silent during lockdown—singing Cranes in the Sky out loud. Incredible moment, and her voice carried that beautiful melody across the quiet night air perfectly. I have a weakness for songs that find a way to make sadness bearable and beautiful and Solange does that here. She’s accepted that trouble is here to stay, at least for a while. That she’ll live through a time when everything hurts then move back into the light.

Cranes in the Sky de Solange. Debo haberlo escuchado cien veces. Había una mujer, de unos veintitantos años, que vivía en la primera planta de los pisos de enfrente. Hablaba con ella de vez en cuando la calle. Debido a las leyes de distanciamiento social durante la pandemia, se convirtió en una especie de Julieta, de pie en su balcón por las tardes de vez en cuando, hablando con algún chico en la calle o visitándola.

Una noche estaba leyendo en la cama, mi esposa estaba en la ducha y Juliet volvió a casa en bicicleta; las calles estaban completamente en silencio durante el encierro y ella cantando Cranes in the Sky en voz alta. Fue un momento increíble, su voz llevó esa hermosa melodía a través del aire rompiendo el silencio nocturno.

Tengo debilidad por las canciones que encuentran la manera de hacer soportable y bella la tristeza. Y Solange hace eso en este disco. Ella aceptó ese problema que llegó para quedarse, al menos por un tiempo. Ella vivirá un momento en el que todo duele y luego volverá la luz.

5 álbumes de los que nunca te separarías y ¿por qué?

5 albums that you would never part with and why?

Only the Lonely by Frank Sinatra. I came into this album via Johnny Mercer and Harold Arlen’s One For My Baby. The intro piano line by Bill Miller is this stage-setting bait that’s impossible to resist. Johnny was very much the poet of urban loneliness, in the same way that Mitski is the poet of millenial loneliness, and the song is just soaked in that. The Mercer lyrics I love all have a couple of things in common—longing and loss. It’s pretty obvious that for Johnny, the only true paradise was lost. His best songs ride the feeling that something good has gone from the world—Skylark, Moon River, Days of Wine and Roses, One for My Baby…these all have loss and longing in spades.

Scott 3—Scott Walker. In the spirit of the times—maybe the business of the times demanded it—Scott kept this astonishing pace and made 5 albums, Scott, Scott 2, Scott 3, Scott 4 and his TV series album, all in the space of about 2 years from 1967-1969. His lyrics were extraordinary and ranged from kitchen sink dramas through to what is the meaning of life? stuff—intensely vivid, fresh images with surreal splashes like “I walk the rooftops, hunchback the moon” or “we’re swallowed in the stomach room”. Completely personal language, completely cinematic. Scott 3’s the one for me—songs that conjure up the most beautiful fog in the world, it’s the album that stops all the clocks.

Around Midnight—Julie London. I moved into a basement in New York that had been previously been rented out as storage for part of some MTV guy’s vinyl collection. The vinyl was still there, lining one entire wall. Life was so busy for him he’d forgotten about the vinyl. I found Around Midnight in his otherwise dull collection and as soon as I played it, I felt like I just wanted to live in Julie London’s world, the lost world of the album. A set of simply stunning torch songs in which the hardest words are spoken softly. It closes with the most devastating version of Betty Comden, Adolph Green and Jule Styne’s The Party’s Over that I’ve ever heard…they’ve burst your pretty balloons and taken the moon away, take off your makeup, the party’s over—it’s all over, my friend.

A Tramp Shining—Richard Harris. Every song by Jimmy Webb, so basically, written by God.

Where Am I Going?—Dusty Springfield This was a very tough call—the Dusty album that’s my favourite changes all the time. But on this sunny Saturday in September, I’d go with this. I love the title track, a show tune with a lyric that’s entirely relatable to everyone at some point in their lives…staggering through the thin and thick of it, hating each old and tired trick of it. Where am I going? Why do I care? Run to the Bronx or Washington Square, no matter where I run I meet myself there.

Only the Lonely de Frank Sinatra. Entré en este álbum a través del disco de Johnny Mercer y Harold Arlen; One For My Baby. A la línea de introducción al piano de Bill Miller es imposible resistirse. Johnny era un poeta de la soledad urbana, del mismo modo que Mitski es el poeta de la soledad milenaria, y la canción simplemente está empapada de eso. Todas las letras de Mercer que amo tienen un par de cosas en común: anhelo y pérdida. Es bastante obvio que, para Johnny, el único paraíso verdadero es estar perdido. Sus mejores canciones transmiten la sensación de que algo bueno ha pasado en el mundo: Skylark, Moon River, Days of Wine and Roses, One for My Baby… todas ellas tienen pérdidas y anhelos a raudales.

Scott 3 de Scott Walker. En el espíritu de los tiempos, tal vez el negocio de los tiempos lo exigían: Scott mantuvo este ritmo sorprendente y logró 5 álbumes, Scott, Scott 2, Scott 3, Scott 4 y su álbum de series de televisión, todo en el espacio de aproximadamente 2 años desde 1967-1969.Sus letras eran extraordinarias y abarcaban desde dramas de cocina hasta ¿Cuál es el sentido de la vida? cosas: intensamente vívidas, frescas imágenes con toques surrealistas como ““I walk the rooftops, hunchback the moon” o ““we’re swallowed in the stomach room ”. Un lenguaje completamente personal, cinematográfico.

Scott 3 es el indicado para mí: canciones que evoca la niebla más hermosa del mundo, es el álbum en el que se detiene todos los relojes.

Around Midnight de Julie London. Me mudé a un sótano en Nueva York que anteriormente había sido alquilado como almacén para parte de una colección de vinilos de un chico que trabajaba en la MTV. Los vinilos todavía estaban allí, cubriendo todo un muro. Su vida era tan ajetreada para él que se había olvidado del vinilo. Encontré Around Midnight en su colección que por lo demás eran discos aburridos y tan pronto como escuché aquel álbum sentí que sólo quería vivir en el mundo de Julie London, el mundo perdido de aquel disco. Un conjunto de “Torch Songs” simplemente impresionantes en las que lo más difícil es que las palabras se pronuncian en voz baja. Y Se cierra con una versión devastadora de The Party’s Over That de Betty Comden, Adolph Green y Jule Styne. “…they’ve burst your pretty balloons and taken the moon away, take off your makeup, the party’s over—it’s all over, my friend”.

A Tramp Shining: Richard Harris. Cada canción escrita por Jimmy Webb, básicamente, está escrita por Dios.

Where Am I Going? Dusty Springfield Esta fue una decisión muy difícil: Mi disco favorito de Dusty cambia todo el tiempo. Pero en este soleado sábado de septiembre, me quedo con este. Me encanta la canción principal, un tema musical con una letra completamente identificable para todos en algún momento de sus vidas… “…staggering through the thin and thick of it, hating each old and tired trick of it. Where am I going? Why do I care? Run to the Bronx or Washington Square, no matter where I run. I meet myself there”.

0 comentarios